‘Materializing the Invisible’ with Susan Giles

Thursday, July 15th, 2021

Chicago, United States

Author: J Rah

Editor-in-chief: Tamy Emma Pepin

Around brunch time on a muggy summer day, Susan Giles, a Chicago-based artist, researcher and educator at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, welcomed ORB into her home to discuss her gesture-based sculpture work.

“You have to come in quick, or the birds will fly out”, she said softly, peering through a slightly-cracked front door.

Just before beginning the interview, Susan invited me to participate in one of her projects, which uses data as a sculpting medium.

With a keen eye, she instinctively scanned and analyzed my every hand gesture and nervous mannerism, capturing my gestures with motion tracking technology. The result was a set of numbers, which are populated as data points for digital sculpting.

Found Gestures (Chicago). Molly Dunson, Ethan Larbi, Ashley Lazaro and Emanuel Wiley speak about Folayemi Wilson’s Dark Matter: Celestial Objects as Messengers of Love in These Troubled Times at Hyde Park Art Center, March 31 – July 14, 2019. Art by Susan Giles and Sally Morfill. (2019, acrylic paint and adhesive vinyl, 35 x 60 inches).

Originally from New York City, and growing up in Jersey, Susan found herself wanting to go somewhere far from home for school. As environmentally different from NYC as she could find in fact.

She took her undergraduate studies to lower density, in the higher altitudes of Colorado, to then go on to postgraduate studies, acquiring an MFA at Northwestern University. She then completed a Masters in Art Education with The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC); the educational branch of what is known as one of the largest art museums in America, The Art Institute of Chicago. After completing her MA, she found herself, unlike her colleagues and fellow New Yorkers, without an urge to return to NYC.

“I wanted space,” Susan added while expanding on her decision to plant roots in Chicago.

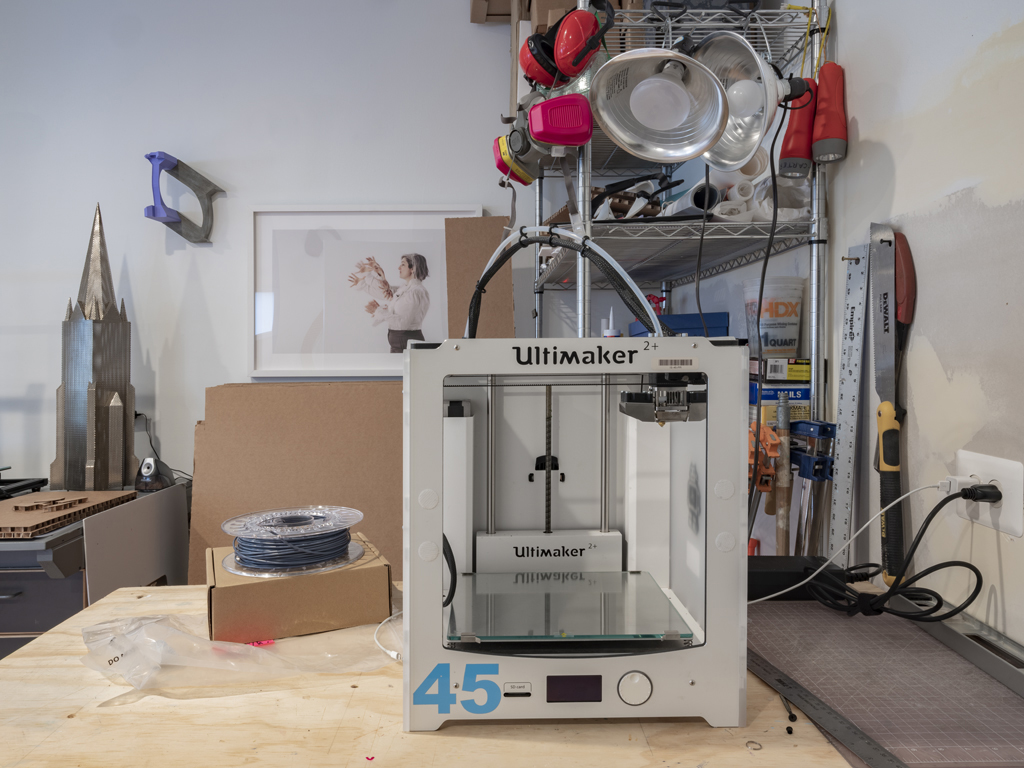

For the following fourteen years, she taught at DePaul University in the Lincoln Park neighborhood of Chicago. When “the right position” opened at SAIC, she transferred. Stimulated by the interdisciplinary nature of the school, Susan was excited to “push in every direction” with tools such as code and 3-D printing in her own work. “It was almost like becoming a student again”, she explains.

We sat in the home studio filled with concrete slabs, 3-D prints and geometric metal models. These sleek materials contrasted with a tucked-away stack of goofy hand-drawn comics. As the back-garden shown through windowed-french-doors formed a softer backdrop, we went on to discuss flexibility in teaching.

J Rah: What are some of the unconventional teaching methods you use, or have come across while teaching, and have these been influenced by your students?

Susan Giles: The approach in class changes with the students. Who are the students — in terms of where they are from, what did they grow up with, what are their expectations regarding technology… if they look at phones and computers as devices for consumption rather than production.

I guess I’m starting with this sort of broad template. Also, the length of our classes contributes to this. We meet once a week, for a bunch of hours, versus meeting twice a week when I was teaching at DePaul. Meeting once a week poses this question of how to maintain that dynamic and keep the activities engaging.

One thing that I love about our department; contemporary practices, is that it’s our job to introduce students to all of the ways of working — let’s really explore, experiment and play. That’s right where I wanted to be with my own work, so I felt like I could do that alongside the students. Let’s do this together.

This challenges me to think, how do I do right by this group?

And then, more specifically, we’ve always cared about being anti-racist as a department. The whole department got together for the first time last summer, to come up with curricular initiatives, work to support one another and make discussion groups for faculty to talk about things. It felt really urgent and needed to step that up, but also really exciting and supportive.

We were able to do that really quickly within ourselves, not waiting for the school to say we have funding for it.

J: Your practice and work explore things such as architecture, gesture and memory. Could you tell us a bit more about how those things relate to each other for you?

S: There is this thing called the memory house. It’s this way of sort of memorizing things by moving through space… I noticed that my memories were really tied to space —

and in fact I think gesture is tied to this. We are inherently spatial thinkers, right? And gesture is where language, memory, thought, cognitio — become spatial. Some studies on gesture, (like David McNeill’s gesture research for example) talk about how in the absence of visuals or space about a memory, people actually gesture more to describe. Gestures help facilitate a visual in the mind, to imagine being in a specific space. Those kinds of things have been very influential for me.

J: So can you describe the relation between interaction and space, how they inform one another?

S: I think space impacts our interaction within it in ways that we’re not even conscious of. Sometimes we are but sometimes it’s more like a gut feeling…

I was just in a Target that was downtown, in Streeterville, and I was feeling really cranky there. I think it was because people kept bumping into me, and you were just bumping into things…and I was thinking about this other Target I go to, that’s just really wide open and I feel like I can just take my cart and start… *makes a side-to-side swaying gesture* you know what I mean? And that’s not even something I’m normally conscious of, or what shoppers are thinking about when they go, but it does impact you and how you feel.

Buildings and spaces can be part of identity. As a Chicagoan, specifically… as an artist in a studio for example. I think we like to think our interaction is not as impacted by space, but it is.

This goes back to architecture. It kinda drives me nuts when people are not thoughtful about how their space is designed. Like my neighbors who’ll pave over their gardens, or thinking about how it feels to walk down the sidewalk when there’s a little bit of breathing room between the sidewalk and you and the building, versus when you’re up against the building.

J: It looks like concrete growing out of concrete.

S: Yea! Emotionally that impacts us and it also impacts the way we move through space.

Found Gestures (2019). Art by Susan Giles and Sally Morfill. Acrylic paint on vinyl adhesive. Photo credit: Tran Tran

J: Looking at your ‘Found Gestures’ project, a collaboration with Manchester-based artist Sally Morfill, I find an importance of tracing one’s steps, like if you were to materialize your invisible impacts. Do you feel like that interpretation is close to what you were looking to convey in these pieces?

S: Yes, absolutely. There’s like this trace of the body… because movement; performative movement, dancing, they’re so fleeting … and gestures in particular are not always what we’re most focused on. We’re kind of operating on a periphery of what we’re thinking about, but they’re there, you see them, they’re communicating to you and you’re understanding things in a different way, so it is about how we hold on to this thing, make it material or visual or almost stop time for that moment so we can hold onto this.

There’s this tiny bit of longing there, too. Longing to connect to something that is always gonna move further and further from us through the distance of time…

J: It’s almost like in Do Ho Suh’s Home Within Home, 2008 installation. He traced an entire house with different materials. It’s like the imprint that place left on his mind. With ‘Found Gestures’, for me, it’s like the imprint that a conversation or feeling left on someone.

I was thinking, to have a material representation of the impact made in a conversation, it conveys a mindfulness of those impacts. If more people were able to experience that, do you think that could encourage a sense of mindfulness or personal responsibility?

S: I haven’t thought about it that way, but yeah, that should be part of it. It’s hard to tell exactly how people receive it, but that seems like a natural way people would receive the work.

J: Like Awareness!

S: Yes, certainly. Even when I start talking about the gesture work, I become much more aware. I start seeing my gestures more. Which is why I don’t like to share very much about what we’re doing before I do a gesture recording… That’s a great question.

J: And yeah, not to make it about someone’s lack of awareness, but I do think for someone who acts with less of a self awareness, to see something like that could let them be aware of how the things they do actually can leave some type of imprint.

S: You might not even be aware. If you look back at the gesture you made in the recording earlier, and see that it was actually this graceful, looping arc, you may not remember it that way but you realize that was a part of your experience of what you’re describing.

J: I’m imagining the gesture behind the shape, and not just the shape now (in reference to the sculptures). What is it about movement and gesture that captivates you?

S: There are certain things about kinesthetic movement like the direction of movement… It would take so many words to describe, but we can make that simple gesture and that gets it across. For me it makes speech visual, and sculptural, and performative, and as a maker, as a sculptor, it’s just… so exciting.

J: I guess that leads to the question of how this observation of gesture and method of making has influenced your material use in sculpting?

S: It’s been really experimental, which maybe comes back to making the most of teaching at SAIC. As a sculptor you’re always thinking, what is the material that’s going to convey this idea the best?

I’ve actually been playing around with 3-D prints for these architectural models and it works well for that. But I also felt like what else is 3-D printing good for? That just felt like a great way to make a model of a gesture… I’ve got this digital data, that’s something the technology of the 3-D printer can do really well, that’s what it’s operating on. These XYZ data points; this is here, this is here, how do we connect these things?

J: Interesting. It’s like using something intangible as a physical material… Like using the other side of technology, one that you can’t grasp, like a screen or object, and using that as a material. In the age of technology and automation : does the human gesture take an even bigger importance?

S: I think so. I was really noticing during COVID, when we were on Zoom, that it was harder, if I couldn’t see people’s gestures, or if they were cut off. I also found that I was gesturing more in front of my face within the screen to try to communicate this information. I felt like there were huge misunderstandings because we weren’t able to see each other’s movements the way we would spatially. And that is something that we still need, technology… just can’t… It can’t be made up. We still have to be in the same space with people. We still need this, live, time, and 3-D space information. That’s what we are as beings in the world.

J: What do you think of the idea of an automated society? How deeply do you think our movements in the physical world are influenced by invisible algorithms?

S: That scares me. And I don’t know where we’re going and I don’t think we know the impact of that yet?… Do we even know how that’s impacting conversation, or with younger generations or kids who have just gone through a year and a half of not being in person ….

J: … and that was like their first ever social interaction outside of their parents…

S: Yea, like middle school where it’s so awkward to communicate anyway. Do we begin to lose that ability as we spend more time through these devices? I don’t think we can become fully automated.

J: What are some of your favorite books and artists whose work has had an impact on your way of seeing and experiencing the world?

S: Well as I was saying before, there’s a gesture lab at the University of Chicago, I follow really closely. In terms of content.

One that pops into my head is Phyllida Barlow, there’s something about the way she transforms space that is really exciting to me… and there’s an improvising with materials in her work that’s really interesting to me. Even though this is all sort of very planned out, I’m really interested in the sort of improvisation that happens within gestures.”

J: How do you think that schools will evolve post-pandemic?

S: I think the pandemic blew open what attendance and engagement means: do we always have to be in person? I do think having some Hybrid learning ready for students that wouldn’t be in person that day, ultimately served the students really well.

Ideally we’re still in person, there’s so much important stuff that happens that way. If this discussion happens best on Zoom, or just as well, then do what you need to. Or would it be more efficient for students who are already set up with a project and it would actually take more time to come into class, rather than to log on and talk about it… Flexibility! That’s what I think. I think some of that flexibility is going to stay with us.

J: Any advice you would give artists today?

S: It’s a hard field. You have to be self-motivated. The importance of the everyday, the work of the everyday, that’s not glamorous… plugging away and working at something, even on those days when you don’t feel like it or you’re tired. I think it’s about chipping away at something.

J: For ORB as a platform, there are three main points: Art, Science and Wellness. Where do these three things intersect for you?

S: That’s a great question, and I love that about this platform. For me the gesture is about science, but there’s psychology, linguistics, technology, all of these other things. But I also think about how gestures are a part of communication and conversation, which are part of wellness. We thrive on human interaction and conversations with other people.

J Rah

jraheem.space

J Rah (Jay Rah) is an interdisciplinary artist, SAIC student and a creative writer at UPPL, a global creative agency, design studio and publisher of ORB. J Rah is evolving in the fields of still and motion image making + score production.