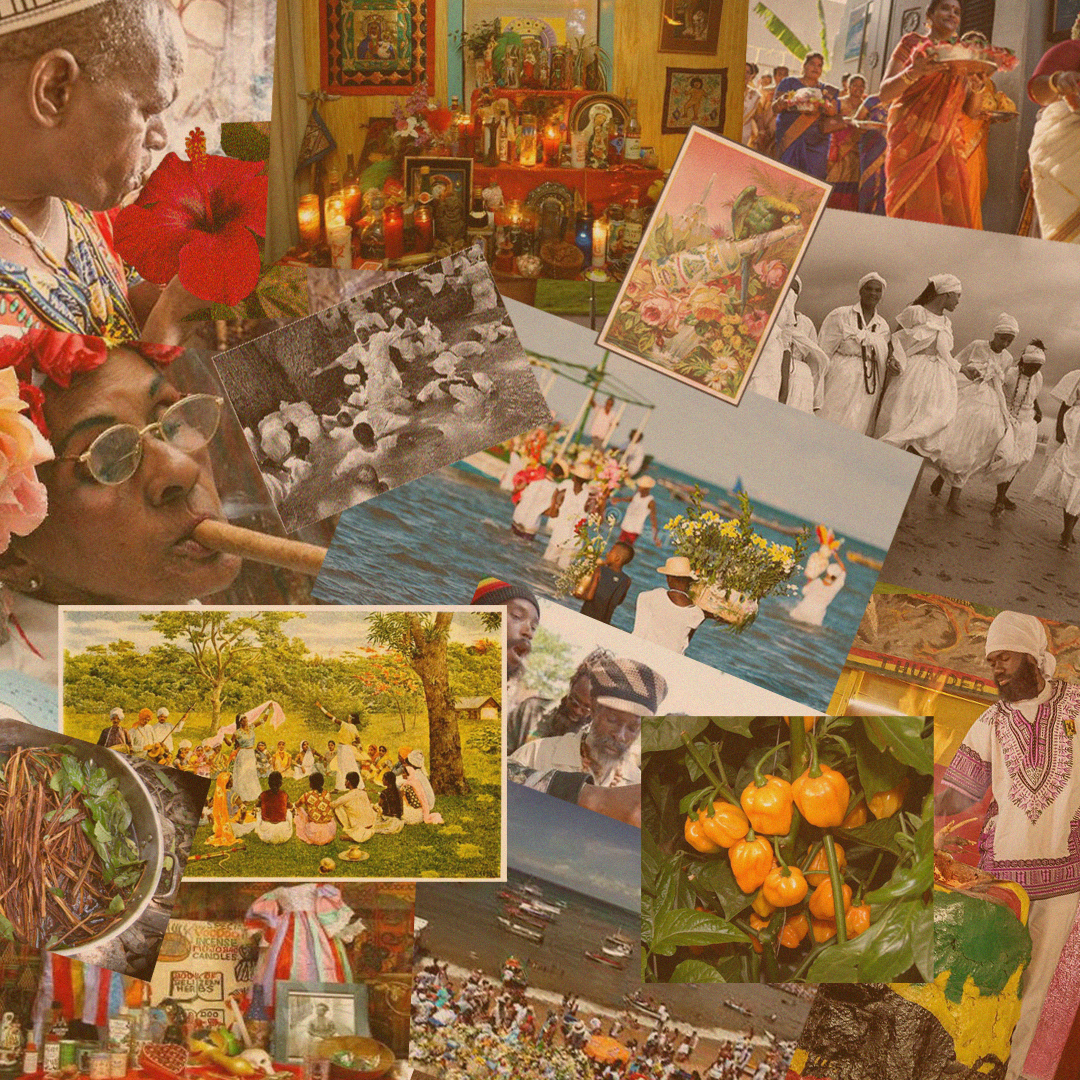

Return to Self:

Exploring Healing through Wellness Traditions of

the Caribbean

Date

Thursday, February 25th, 2021

Location

Montreal, Canada

Author

Chelsea L. Niava

Editor

Fatou Alhya Diagne (Guest)

Editor-in-Chief

Montreal, Canada

Illustration

Saraah Bikaï

There are certain things that all children of a Caribbean household learn at a young age. If you disobey the rules there will be physical consequences, you eat what was prepared for you, before bed you bathe and pray, and never forget to respect your elders. As you grow older you will find some other customs that are similar across the Caribbean, and yet not as openly spoken about.

These are wellness and spiritual traditions that have been carried on throughout the generations. I have noticed that whether you are of African, Indian or Latin descent, these practices include herbal concoctions for any and everything, various ways to protect the home from undesired spirits, fasting, massage, and of course, our infamous celebrations of Carnival where the dark folklore spirits, such as jumbie are equally celebrated as the daytime bright feathered characters, both of which connect us to nature. Over the years I have been demystifying this ancestral knowledge and digging deeper into my Caribbean identity, and my deep connection with nature that has been fostered through this culture. The way I see my work as an infant massage instructor, touch and attachment researcher, ayurvedic massage enthusiast and poet is strongly through a lens of Caribbean wellness and nature.

Separating my understanding of wellness and spirituality seems impossible. Similarly, I cannot discuss my Caribbean identity without exploring blackness and the traditions that melt together on these islands. Stories of the Atlantic slave trade, the common diasporic trauma and the rituals that we managed to memorize must be explored. Though I have been distinguished as a “coolie” (a derogatory term that was used by the British to identify Indo-Caribbeans), I currently sit here in West Africa researching wellness practices in the Caribbean, and I see so many similarities between my husband’s home and my own. So, I’d like to take a moment of gratitude for my black brothers and sisters, and express my humble heart for the opportunity to share this piece for Black History Month. So, where did it all start?

Beginning in the 1500s, there was a rise in the amount of enslaved people, as the Spanish capitalized on the Caribbean indigenous tribes, both Arawak and Carib, disappearing due to European diseases4. Transportation of the enslaved West African people went from two to three, to 200 to 300 and more4. With different customs coming together, a unified sense of blackness maintained well-being in this new land. The indigenous peoples and Africans worked together to survive spiritually11.

Eventually, the enslaved African people began to incorporate Catholic tenets into their own beliefs1. This led to the creation of religions and practices such as the Santería which attempts to synchronize Christian and Yoruba (a tribe and religion belonging to West Africa) traditions. This blend of traditions allowed the Caribbeans in the regions of Cuba and Hispaniola (Haiti and Dominican Republic) to discreetly practice their West African traditions behind the dominant religion, Catholicism. Yoruba Priests and Priestesses would use church grounds to practice their ceremonies and bury the dead, leaving the earth to carry their ancestors’ powers1.

Caribbean pharmacies were filled with simple (unmixed materials) and recipes hailing from places as far flung as Java, Goa, Brazil, Angola, and the Philippines, as plantation crops grew and diversified throughout the seventeenth century4. Not only were forms of wellness transforming, so were the resources and ingredients of medicinal treatments. West Africa, India, as well as in Portugal, and Spain, and other Atlantic and Caribbean locales, came together to form the most abundant region of health practitioners at the time4. The Caribbean was a large port where spices, herbs, seeds, bark, fruit and vegetables were exchanged. With the East India Company founded in 1600 and the West Africa Company founded in 1660, both owned by the British, the Caribbean became a place where the origins of food, culture and spirituality could no longer be distinguished.

This combination of Euro-centric values and African rituals may have once allowed the enslaved people to practice their traditions safely, however, this combination also led to the demonization of more spiritual forms of healing such as Voodoo and Obeah5. The traditional healing and spiritual practices of the diaspora continued to be condemned throughout the centuries.

Within the next 100 years Indian indentured laborers would arrive in the thousands, making up the second major ethnicity across the Caribbean countries, and the majority in some countries such as Guyana, Trinidad and Suriname2, 10. This new ethnic group that was promised land brought with them Hinduism, Islam, a plethora of spices and Ayurvedic healing practices. With their strongly founded spirituality and healing rituals that could not be well explained, Obeah became a word that was commonly used in these communities. Obeah and Voodoo seemed to be the most condoned practices as they were associated with summoning spirits, and most of all because Obeah men were rumored to provide Anglo-Caribbeans with spiritual protection and courage to fight the British Colonial authorities8 who were openly participating in the erasure of black ancestral culture6. While these specific soul strengthening practices were grounded in blackness, and were thus not permitted to thrive, they somehow managed to survive.

By the 19th century, hoards of both Afro-Caribbeans and Indo-Caribbeans were being ostracized, publicly humiliated and eventually imprisoned for their spiritual practices6, 8. Obeah became illegal and many rituals were lost. Similarly, around this time, Voodoo was also outlawed, and even midwives were suspected of sorcery1.

In the 20th century, we saw a new wave of spiritual practice and well-being called Rastafarianism, which started in Jamaica. Interestingly, the Indians that settled in Jamaica had a large influence on this practice. Introducing their neighbours to vegetarianism, mediation, and an herb they called “ganja”, which was used to soothe a variety of ailments, and to reach spiritual enlightenment7. This is a perfect example of how traditional wellness practices in the Caribbean were brought together through a common identity of blackness.

Though it’s difficult to track the geographics of materials used, and ethno-national identities of who influenced who, it is evident that the Caribbean is based on African rites and rituals, combined with deep levels of European, Indian, and Indigenous influences4. This shared ancestral knowledge and diasporic identity allowed each of their customs to grow and transform together as one, which likely went against the colonizers’ desires. Due to stigmatization, many practices have been shared orally and remain understood yet inexplicable.

However, the ways in which each healing practice seems to share similarities perhaps can be explained. It is important to note these similarities, because despite the forced necessity to once hide behind our euro-centric assimilations that have separated us, we continue to be identified as a common people, and should we not be? Of course, throughout the Caribbean, there are differences that make each island unique, despite this there is a common thread that has kept us all full of soul over the centuries.

Six themes have emerged under Caribbean traditional healing and wellness interventions; diagnosis, treatments, cleansing rituals, worship, healing ceremonies, and mechanisms of healing and transformation of trauma and suffering11, 12.

Throughout all of the above mentioned wellness practices in the Caribbean, there is the initial meeting, whereby a spiritual leader, shaman, pundit or other, will assess your current state. Spiritual healing can take many forms depending on what you are suffering from. For this reason many spiritual leaders will refuse treatment before a consultation. Diagnoses can vary from forms of energy imbalance, ancestral trauma to poor diet. Once your spiritual and physical state are assessed, you may then move on to being treated.

Across the Caribbean, treatments involve a wide scope of cleansing, which normally includes some use of natural elements, such as water, air, earth or fire to release any evil spirits and bring one’s health back to balance. Water cleansing rituals can occur by either visiting the ocean and honoring the water through Orishas like Yemaya in the Santería and Voodoo practice, or Varuna in Hinduism. Sacred baths are also commonly seen among traditional practices within the Caribbean. These baths usually include special blends of flower water, salt, and herbs prepared either by an elder in the community or a spiritual leader. Using smoke to cleanse homes, temples, and other spaces can be seen across the Caribbean as well. Some materials commonly burned were palo santo (Santería), sandalwood (Ayurveda), bwa pen (Voodoo), and candles. Finally, herbal potions and plants continue to be popularly used throughout Caribbean practices. They include bush teas, which are made up of different local herbs and usually caffeine free. Cannabis consumption and other complex tinctures such as ayahuasca are used for spiritual transcendence. These concoctions can have gentle to more abrasive symptoms, however, they all include a form of inner healing that is meant to lift the spirit and bring one closer to self.

Although prayer and meditation may be practiced differently, having faith is highly valued in the Caribbean. Some traditional practices pray to multiple gods and goddesses, orishas and spirits, while others remain faithful to one overcompassing energy. However, wellness practices always include a moment of dedication to the “most high”. States of silence, meditation or worship are also common and can be practiced in groups.

Ironically, many of us continue to pray to God and other deities, get together in healing circles and attempt to break intergenerational curses, and yet, also blindly accept our whiteness that maintains our class systems, our privileges and our separation from one another. This is why above all, it is not just anyone in the community who has the power and rights to offer advice and guidance. Those who have been chosen must endure moments of deep fasting, isolation and ancestral education4.

Through what I would describe as a soul screaming desire of knowing who I am truly and deeply, I have been through levels of isolation and education. During these periods, I discovered my ancestral alignment with Ayurveda, and my unwavering connection with West African practices that continue to thrive throughout the Caribbean islands today. As a Caribbean woman, I have often felt misplaced in my identity. Though I am Indo-Caribbean, I am certainly not Indian, and I am sure of this, because on multiple occasions I have been rejected by the South Asian community for my Trinidadian background. Interestingly enough, I’m also half Sri Lankan, but my “mixed” ethnicity had trouble belonging. Many people have assumed I’m black. While growing up I felt that I had almost offended some family members by thinking this to be true. Today I am almost apologetic when I am mistaken for Afro-Caribbean, and yet frustrated when I have to distinguish my Indo-Caribbean identity from being Indian. In my own personal healing journey, I found it necessary to unveil the intergenerational traumas that have persisted through the adoption of whiteness. The whiteness that if interested, would allow me to hide behind some sort of false privilege. Decolonizing my wellness practices and unlearning my self-sabotaging tendencies required assistance.

Thankfully and by no coincidence, I magically fell upon strong black Caribbean healers, one of which is called Gytana T. Light. She is no ordinary healer, she comes with the Caribbean aunty attitude, she will put you in your place, while holding you gently as you walk through the ancestral shadows. Despite the current trends and popular use of sage and crystals, she brings another level to these earthly materials. Temple KÀ is where you can find her. A celestial holistic spa, a place that she has managed to expand and grow over the years. When I walk into this space, there is a certain aroma of the herbs my mother burned regularly, oils meant to help you rebalance, and most of all healing happening in every room you step into. Sacred baths, yoni steaming, oracle readings and energy healing are common practices at Temple KÀ.

To help enrich my research and perspectives of this extraordinary collection of islands, I asked Gytana if we could connect over zoom. Even across oceans, I could feel this Queen’s presence’, her voice resonated throughout my room and I knew that I had so much more to write than I imagined. She reminded me of the magic in the Atlantic waters, the suppression of self that all Caribbean folk have passed through, the wonders of nature that have allowed us to travel into new dimensions of healing, and the need to return to self. And yet, I still hadn’t found what I was looking for until I asked her to clarify what she felt made wellness in the Caribbean so unique. She said, “Of course our similarities matter, but that’s not what it is.” And then she made this distinction that will forever leave a pounding of pride and solidarity in my heart and soul. “It is our blackness,” she said. It is our blackness that maintains our perseverance to heal, to search for wellness practices, that allows us to reach the depths of our trauma. It is our blackness that pushes us through our darkness and into the light. We stand strong in the dark because we have been there before. And it is our blackness that calls us to return to self. The journey back home is not necessarily to our homeland, it is into our soul, it is where we find mental and spiritual liberation. Our blackness is what creates the authenticity in our wellness practices and what permits us the power to exchange our godly knowledge and heal together.

Chelsea L. Niava

Chelsea, founder of @higher.veda, has been committed to healing families and individuals through different healing practices, including massage, ayurveda and poetry. Unpacking her Caribbean identity has lent extraordinarily to her vision of wellness, and has led to a journey of breaking intergenerational trauma, both for herself and her community.

Bibliographie

3. Forbes, C. (2014). Caribbean women writing: social media, spirituality and the arts of solitude in edwidge danticat’s haiti. Caribbean Quarterly. (60)1, 1-22. DOI: 10.1080/00086495.2014.11672510

6. Hutton, C. (2019). Introduction: african-caribbean spirituality and creativity. Caribbean Quarterly, (65)2 207-211. DOI:10.1080/00086495.2019.1606990

10. Roopnarine, L. (2006) Indo-Caribbean Social Identity, Caribbean Quarterly, (52)1, 1-11. DOI: 10.1080/00086495.2006.11672284

11. Sutherland, t., P (2017). Cultural Constructions of Trauma and the Therapeutic Interventions of Caribbean Healing Traditions.